Contributer: Sara Fogarty

Last year as part of the Houston Foresight Masters program I took a class on Design Futures. Our final assignment was to create an experiential future for our annual alumni gathering. If you are not familiar with experiential futures, it’s a way to facilitate a visceral reaction to what a possible future could be including tangible artifacts and engagement of the senses to bring the vision to life.

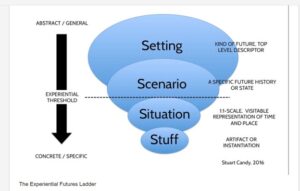

One of the draws for me to Foresight or Futures Studies is the abstract ideas inherent in the field, however, as Stuart Candy and Jake Dunagan explain, experiential futures work bridges those abstractions into the objective futurists strive for – creating possible, plausible and preferable futures that can be touched and felt – concrete. Stuart has created a model called the Experiential Futures Ladder to guide the thought process when developing an experiential future for an audience.

The experiential future design group I was part of with a few of my classmates focused on the Future of Death. Each of us brought with us our own angle for having curiosity about and wanting to find meaning in this topic. My own reasons were very personal. I grew up in a family of seven and four of my family members have passed away, three of them suddenly. As many people can relate, these life events not only provided the stark reality of my own mortality, but also the struggle to navigate grief.

For some, death is an uncomfortable subject – thinking about the end of our own mortality. Imagining what we cannot see, realizing what we are experiencing right now, will not exist when we die. The realization that we are part of a cycle of life, not outside of it, not being able to control it, can be unsettling. The compelling question here is our relationship with death. There are alternative futures that are possible to alter the way our physical lives end, and as a result affect our feelings toward death.

Environmental concerns are driving new ways of thinking about what humans do with our bodies at end of life and was one of the elements that drove the scenarios for my group’s experiential future at the event. There are many articles written about the toxicity to the environment of the chemicals used in embalming like formaldehyde, phenol, and methyl alcohol, which can leach into the soil eventually. Additionally, the casket material used for burying in cemeteries can take 50 to 100 years to decompose in the soil and dying isn’t free – the low end of the spectrum to be buried is $7K to $10K. In an effort to combat the space and cost hurdles, in the United States cremation has now become the most common choice for death rituals, however the procedure releases 250 pounds of carbon dioxide into the air. So, if you care about the earth, cremation is not the best option available.

Our design futures team created an experience to become familiar with several types of alternative options to transfer our physical forms back to the earth. Some of these options are starting to emerge and could very well become the norm in our future. How would you like to see your passed on beloved lighting up the Brooklyn Bridge via anaerobic microbial digestion? After all, everything in the universe is energy, so in the future our physical beings could be converted into light.

Another option is alkaline hydrolosis or aquamation, if you like the idea of a gentle, water based cremation where your body is turned into liquid. Family members can keep the liquid version of you in decorative vessels or use it to water a memorial plant in their garden.

Natural organic reduction (NOR), otherwise known as human composting, is the method I focused on for our group’s future of death experience. Human composting is legal in six states. Washington was the first only recently in 2019. Along with that first the company Recompose was the first facility in the United States to provide NOR services to customers. Proponents of this method have the perspective that it is a natural, peaceful exit to be laid among straw and wood chips for 30 days while the body breaks down into soil, like a tree that falls in the forest.

The united states is one of the last countries to favor burial. Is the way we die in our country an extension of the individualism our nation favors? We all need to have our individual casket in our own piece of land – taking up space even when we are no longer breathing? A different, more collective view of burial could be a possible a future.

I heard a saying recently “what is precious must end”. Let’s face it – a lot of what the ritual of death is about is for those left behind, those who grieve. Rather than be placed in my own dark box buried in the ground, I prefer to go through a process to integrate back into my natural ecosystem, returning my energy to the universe. Instead of grieving the loss of never seeing a family member or friend again, in the future it would be wonderful to look out into my backyard and see my orange tree thriving with mulch from my brother, or return my mother to the redwoods I visit in her liquid form, and leave behind to my children my own field of poppies in remembrance.