“Ours is a brand-new world of allatonceness. “Time” has ceased, “space” has vanished. We now live in a global village…a simultaneous happening.” -Marshall McLuhan, The Medium Is The Massage (1967)

The fact that you are reading this not in a book or were spurned to read this through electrical circuitry through the expanse of Facebook or Twitter spills the irony water flow over the glass like Marshall McLuhan would have seen.

Our global connectiveness and the never ending stream of online perpetuity has claimed a world consciousness. Twenty four television, reality shows, streaming live data, cellular service, instant information, and the promotion of the Westernized world into every facet of reality on Earth has not stopped since Canada’s favorite futurist weirdo wrote his first book on media in 1951, The Mechanical Bride, an extensive examination of popular culture when popular culture was just starting to take off. Most people though have no idea who McLuhan is, and how his thoughts go hand in hand with what our “global village” has begun today.

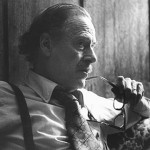

To many Herbert Marshall McLuhan was an explorer of the word and language, a constant searcher of the meaning of our mediums. By 33, McLuhan had already compiled two sets of BA’s and MA’s from the University of Manitoba and Cambridge, finishing his PhD from Cambridge in 1942. He had began to teach English literature to students at the University of Wisconsin in the mid-1930s when he began his directions toward pop culture and used his thoughts on the advertising of the day to compare great literature to his bored American students. His critical analysis of the pop-up world his students lived in with cigarette billboards and vacuum radio jingles permeating their pathways enabled him to parallel his literature world to their world. McLuhan saw that their was no difference in the message world, only in the information that was being pushed.

“Because all media, from the phonetic alphabet to the computer, are extensions of man that cause deep and lasting changes in him and transform his environment,” McLuhan said in a 1969 Playboy magazine interview. “Such an extension is an intensification, an amplification of an organ…the central nervous system appears to institute a self-protective numbing of the affected area, insulating and anesthetizing it from conscious awareness of what’s happening to it. I call this peculiar form of self-hypnosis Narcissus narcosis, a syndrome whereby man remains as unaware of the psychic and social effects of his new technology as a fish of the water it swims in. As a result, precisely at the point where a new media-induced environment becomes all pervasive and transmogrifies our sensory balance, it also becomes invisible.”

If you have no idea what McLuhan is talking about, take a number. At the time of his numerous books, interviews, and television appearances, Marshall still could not be completely understood. His language spoke in code, and he himself seemed somewhat pleased to be the smartest person in the room. At his apex in the human media world in the late 1960s and early 1970s, McLuhan’s strange ideas drenched the same media culture he often lambasted. He basked in their glow while news men and television presenters just tried to get a hold of what he was talking about.

It was after the release of his third book, Understanding Media, in 1964, that McLuhan thrust himself on the public domain that he wrote about. While the counterculture roared to find meaning past the turbulent 1960s, McLuhan rose as a messiah of the medium, a truth seeker whose hard to understand ideas fit nicely with live free mantra of that time. Everyone wanted to see and be seen with McLuhan as Warhol, John and Yoko, Dick Cavett, and many others all made their play for the man.

One could see why. He was exciting. He said crazy things. He always sounded like some guy from the future using terminology that you knew, but piecing phrasing together like no one could really quantify. Take a look at these quotes that I put next to things he knew nothing about to give you insight on where he thought we were going, and you be the judge of his prophetic ways:

Google and search engines: “Instead of buying a book, you will go to the telephone and describe you interests, your needs, and your problems…and all at once with the help of computers, they will xerox all your materials to you personally. (1966)

Facebook and Identity: “In the new electric world, where everybody is involved with everybody, where everybody is involved in complex processes, the old identity cards, the old means of finding out who am I, will not work. (1968)

The Connected World Information World: “The global village is not created by the motor car or by the airplane. It is created by electronic information movement.” (1968)

Retro-Revivals: “Because we ordinarily what we see in the present is in the rearview mirror. What we ordinarily think of as the present is really the past. Content is always the previous medium. It is impossible for man to look straight at the present because he is so terrified by it…and so revivals are everywhere today. Revivals of clothing, of dancing, of music, of shows, of everything, we live by the revival. It tells us who we are or were.” (1968)

24 Hour News, Twitter, and the Instantverse: “You no longer have to be everywhere in order to do everything. The same information is available at the same time in every part of the world. The world is now like a continuing sounding tribal drum where everybody gets the message every time. A princess gets married in England, boom, boom, boom, go the drums.” (1966)

McLuhan died in 1980 after a life as a trend predictor, future poet, educator, and even a provocateur. It’s a shame more people don’t know about him, or maybe, he was there all along, a phonetical resonance that remains for us to keep uncovering for another 100 years.

Herbert Marshall McLuhan’s (1911-1980) life and works will be on display in different mediums around the world this year. Check out this website to get a peek of a truly daring futurist.